A Trunk in the Attic

by Taffy Cannon

I wasn’t looking for a coonskin cap when I walked into the gift shop in the Cascade Mountains of Oregon last summer. But straight ahead stood a furry six-foot tree of them in various sizes and I knew immediately there was no way I’d leave that shop without one.

Why? I can’t exactly tell you, though I’ve always loved playing dressup. I never had a coonskin cap as a kid, though my husband did, back when they were all the rage and everybody was singing about Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier. I dressed in Annie Oakley buckskins back then, with fringed vest and skirt, a spiffy cowgirl hat, and shiny six-shooters on each hip.

Before I ever started school, I was photographed as a bride with lilies of the valley pinned to my veil above each ear, a “fierce witch” who was anything but, and a nurse. I wore nurse costumes so regularly that I can still whip up a nurse’s cap out of a sheet of white paper, faster than you can say “Cherry Ames.”

I loved reading about kids who had trunks of old clothing in their attics, usually dresses with bustles or elaborate hats, since our attic held only a few random boxes and my father’s WW II Navy great coat. Alas, I never actually knew anyone with an attic costume trunk, outside of fiction.

Every Halloween we wore our costumes back to school after we went home for lunch. Sometimes mine were store-bought, but mostly they were put together by a clever mother who sewed, and designed to be worn under a coat. Late October in Chicago carried the occasionally-realized threat of trick-or-treating in the snow, as we meandered up and down neighborhood streets, collecting mountains of full-sized candy bars, and apples, and an occasional cupcake.

Dressing up for Halloween went on hiatus in high school, but the die was cast. In college, I instigated any number of dorm skits where we dressed up as, for instance, The Seven Deadly Sins. I believe I was Sloth. Our hall parties to commemorate “the drinking rule,” allowing alcohol in the women’s dorms, always had themes. My favorite was when we all came as our favorite dirty words. I was a popped cherry.

Adulthood might not have brought maturity, but it did offer occasional opportunities for costume. Wearing a very respectable nun’s habit assembled from white sheets, just like Audrey Hepburn in the Congo in The Nun’s Story, I once had an unexpected bad drug experience, at the hands of a very lapsed, masked Catholic.

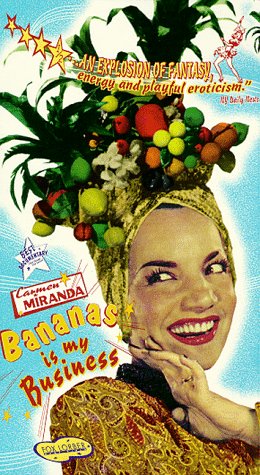

Then I moved to Los Angeles in the late seventies and discovered that adults routinely dressed up for Halloween, and not just for parties, either. They wore costumes to work. You might glance over on the freeway to see a gorilla at 8 am, or wait behind a dude with a bloody axe in his back midday at the 7-11. Nobody’d even blink. This was the period, I’m proud to say, when I was Carmen Miranda in a black wig, slinky dress with ruffled train, and large hat loaded with real (and heavy) tropical fruit. In 1980, I slipped into a black velvet evening gown and gazed adoringly at my mate as Nancy Reagan.

And that, I think, explains my fascination with costumes: the opportunity to briefly become somebody else. It is closely akin to the way writing fiction allows the assumption of all sorts of alternate identities. In the course of a single book, and sometimes even a single day, I can be a dozen very different people, slipping in and out of their worlds, utterly immersed in those characters.

Real life is trickier.

Having a child provided greater license to dress up, though I learned to be careful about the elementary school Halloween Carnival. The year I dusted off some old political buttons and a flowing, tie-eyed skirt, then parted my hair in the middle with a headband, seven-year-olds all thought I was an Indian. But there was no confusion the time I pinned up my hair, donned a neatly pressed work shirt, affixed a holstered glue gun to my hip and wore a name badge that proclaimed: “I am Martha Stewart and you will never be as perfect as I am.”

My favorite costume of that era arose out of my third-grade daughter’s fascination with Felicity, the American Girl character who lived in Colonial Williamsburg. That year I had way too much time on my hands and made us both colonial dresses, clothing that we took to Williamsburg several times and wore around at night, pretending it was 1775.

Our nighttime prowling led indirectly to one of my favorite scenes from my mystery Guns and Roses, which itself grew out of those family trips to Williamsburg. My daughter was perched on a bench outside Chowning’s Tavern, peering through a window at diners eating Brunswick stew and fried chicken, when people inside the restaurant began to notice her in astonishment. I could see the mental wheels rolling: Cut me off, Ethel. I just saw a colonial child. Today Williamsburg is loaded with kids in colonial costumes, which you can even rent, but back then only the staff dressed up, and none of them were children.

That was the moment that I realized I had to find a way to get a book out of those experiences.

Our Friends of the Library host a Halloween volunteer appreciation luncheon, and it is always a treat to see normally very proper volunteers from the Friends Bookstore in full regalia. Some years I just get by (a shirt emblazoned “Security” with a ball cap and plastic club, for instance) but other times I’ve been a fetching haloed angel and once I wore all black with ebony feather wings and a name tag reading “Nevermore.” It was, after all, the library.

This year? The coonskin cap, of course. I’m short on buckskins at the moment, but have homespun-colored jeans and shirt, as well as some fine scraps of fur for adornment. The fur scraps came out of my own attic costume box. Because it’s never too late to create your own costume trunk, and I’m pretty sure this isn’t something I’m going to grow out of.

Nevermore.