Getting on the Bus One More Time

by Taffy Cannon

I’m going back to prison for the fifth time next Friday, and I can’t wait.

This trip to the Central California Women’s Facility has very little to do with me and everything to do with a lot of children who miss their mothers desperately. I’m a volunteer with Get on the Bus (GOTB), and we take kids to visit their incarcerated moms for Mother’s Day, a program that is both heartwarming and heartbreaking.

What happens to children when their mothers go to prison?

I’d been writing crime fiction for some fifteen years and reading it for most of my life when I first heard this disarming question, stunning in its simplicity. I was shocked to realize that it had never once crossed my mind.

In 2000, Sister Suzanne Jabro and the Sisters of St. Joseph were listening to the women they served in their prison ministry, women who thought of little else. These mothers desperately missed their children, mostly being raised by aging or disabled grandmothers, and they knew firsthand what kind of trouble their kids could get into. Often it had been years since they had seen their children, sometimes since the moment of arrest.

But taking children on prison visits is complicated, and in California can involve hundreds of miles of expensive travel, motel and food expenses, as well as complex paperwork that must be completed properly in advance Or Else.

Sister Suzanne started small. That first year, Get on the Bus sent seventeen kids to see their moms for Mother’s Day. A decade later in May and June of 2011, 1357 children rode 56 buses to visit both mothers and fathers in nine prisons across the state. The GOTB program is free to children and their caregivers and the nonprofit organization relies primarily on volunteer organization and fundraising. A recent expansion into visiting men’s prisons for Father’s Day offers plenty more room for growth, since women represent only about five percent of the state’s prisoners and an estimated 200,000 California children have a parent in state prison.

Our buses travel farther than any of the others, nearly 400 miles from San Diego to the dusty town of Chowchilla in the central San Joaquin Valley, home of California’s two largest correctional facilities for women. This requires a predawn departure in order to reach the prison by late morning, in time for a three-hour visit including lunch in the Visitor’s Center, followed by another eight hours southbound. It makes for a very long day.

The entire operation is a bureaucratic nightmare, with endless hurry-up-and-wait over months and months. All of the power lies with the prison system, of course. An inmate may be transferred right before Mother’s Day, or gets into trouble and have her privileges revoked right before the visit. Paperwork sometimes gets lost or improperly recorded, and there are always various last-minute crises. Last year the customary special Friday GOTB visiting privilege was denied and we were crammed in with the regular Saturday visitors. And back in 2009, the entire prison system went into lockdown when an inmate in a facility down by the border contracted swine flu.

But what’s the point? We all know the adage about being willing to do the time if you do the crime. These women got caught. They were arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced, often to mandatory terms for drug-related crimes.

A compelling case can be made for many that their primary offense was poor choices in men, but once their own bus—the one with the grilled windows and D-rings—pulls behind the razor wire, it’s too late to do anything about that.

Meanwhile, their children are sentenced, too.

It’s lonely being a kid with a parent in prison, not something you can talk about or somebody you can bring to Back-to-School night. All of the thousands of tiny elements that comprise the mother-child relationship are compromised by incarceration, and many are totally obliterated. Time passes, memories fade, and release dates somewhere in the dim future seem impossibly far away. Ties that may have already been fragile when a woman broke the law can fray beyond repair under the pressures of time and distance.

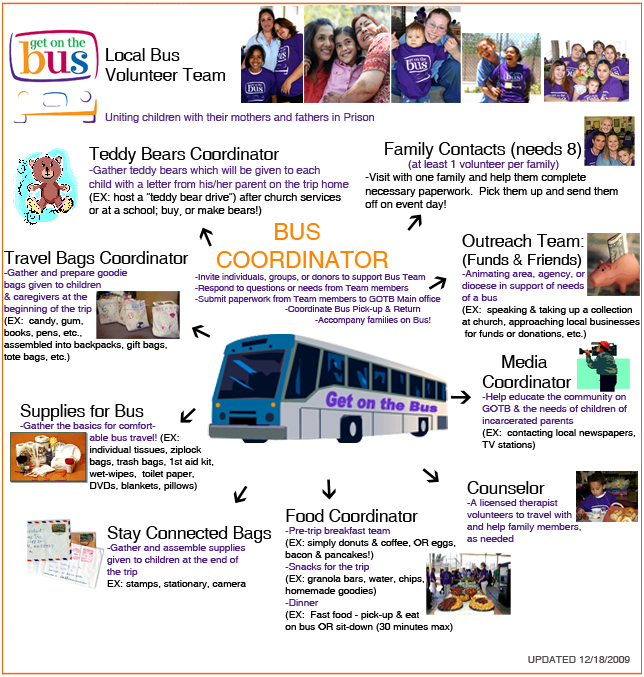

And that, I think, is why I do it. Why I volunteer year after year, for families I don’t know and may never see again. Why I ride 800 miles on a bus distributing breakfasts and snacks and backpacks filled with activities on the way up and passing out teddy bears to clutch on the long ride back home, as the mothers who brought us all together recede into the night behind us, in many cases for another full year.

I want these kids to catch a break. I want these often-dysfunctional families to make it through this particular nightmare period and bring Mom back home to some semblance of normalcy.

The first year I rode the bus, I watched a young woman run to greet her three children in a tableau lifted from a greeting card commercial. The older boy looked about eleven and a younger girl and boy were maybe five and four. She scooped the girl into her arms, waist length hair flying, and swung her daughter in giddy circles.

As I observed them through the afternoon, I was struck by what a typical family unit they appeared to be. They might be on the school playground, or picnicking in a hometown park, or getting into an SUV for soccer practice. When the little boy slipped away into the crowd, his mom was there a moment later, retrieving him. When she darted out of the playroom and found him trying to put a Monopoly twenty into a vending machine, I told her how much I’d enjoyed watching her with her kids.

She thanked me and said, “I’ve never been away from them before. I was always with them, everywhere. You can’t imagine how much I miss them.”

As the visit drew to a close, I saw her inside the children’s play room on her hands and knees, picking up a hundred small pieces from a spilled game, and suddenly she wasn’t an inmate and this wasn’t a prison. She was a mother with her children, and she looked like a mighty good one.

I wanted to send her home with them, right that very minute.

The next year, I wasn’t able to get on the bus, and when I returned the year after that, I looked for her and her family. They weren’t there, and I never saw them again. I like to picture them in a park somewhere in California, laughing.

[Photographs courtesy of Get on the Bus.]