Preparing to Flee

by Taffy Cannon

A few years back, a fast-moving wildfire driven by Santa Ana winds and fueled by brittle mountain chaparral bore down on the area where my daughter was living north of Los Angeles. When she called me, her fiancé was headed home from the nearby Cal State campus, which was rimmed with flames and under a mandatory evacuation order. Once he arrived, they intended to leave and stay with his family in Los Angeles until the danger passed.

What, she asked, should she pack to evacuate?

It’s a question many of us have asked when under siege by the unholy trinity of natural disasters: fire, flood, and hurricane. Sometimes these situations come up too quickly to respond to, or we wait them out too long, and they are certainly never convenient. And sometimes there just isn’t anywhere to go. A friend in South Florida pointed out a few years ago that attempting to avoid a hurricane larger than the state of Texas was the ultimate exercise in futility.

For the most part the unholy trinity provides sufficient warning to allow some kind of response. Tornadoes and earthquakes don’t offer that luxury, though with a bit of luck folks in the path of a tornado can reach safety or a storm cellar and people in an earthquake can get to a doorframe or duck under a table.

Voluntary or mandatory evacuation orders have become increasingly common in the face of impending natural disasters, which makes a lot of sense. First responders need to be able to get in and do their jobs without interference and drunks at hurricane parties and stubborn holdouts facing down flames will only need to be rescued later anyway, at greater peril to everyone. In my community evacuations are now announced by robocall and text message, though thankfully not often.

Fire season in Southern California is a strange and evil dragon.

As the hills parch, natives watch uneasily for Santa Anas blowing in from the desert, aware that all it will take as those winds move through the canyons is a single spark. Almost anywhere.

The days when firestorms begin often start out with deep blue skies and pleasant, unseasonal warmth. You’ll be thinking what a gorgeous day it is when you suddenly catch a whiff of smoke on the breeze and immediately begin scanning the horizon in every direction, looking for the telltale swirl of smoke.

I remember standing at my Venice kitchen window as a thick and oddly beautiful white plume crossed a periwinkle sky to announce the Malibu fire of 1983. That was the first fire season I was aware of from the beginning and it was a bad one. I wasn’t caught entirely by surprise, however. On an earlier November visit, I had awakened one morning to discover a layer of fluffy white ash on my car, wafting in from a fire in the Angeles National Forest.

These fires tend to be driven by hot and brutal winds, racing through areas with very little development and lots of dry brush. They often are started by banal causes: poorly tended campfires, errant kites, downed power lines. All too frequently several blaze simultaneously on those days featuring the poorly named “perfect” fire conditions. And yes, on those days pyros sometimes set copycat fires and sometimes get away with it.

So long as the fires are off in some forest or another, it’s distressing and the air gets nasty, but that’s what happens when you live in this part of the world. It’s when wildfires dip into residential areas that things become truly terrifying.

Neighborhoods burn, sometimes in random hopscotch patterns. Automobiles explode. People awaken to bullhorns in the middle of the night and escape in their pajamas, inches ahead of the flames. Evacuation centers materialize in high schools, community centers, and stadiums. Horses are evacuated to the Fairgrounds. Pets are lost in all the noise and fire and fear and confusion, sometimes never to be seen again.

I never thought about the possibility of fire evacuation when I lived in Venice, even though I knew there’d been a fire in Bel Air that affected Richard Nixon back in 1961. There was so much urban sprawl between me and any obvious wildfire location that it wasn’t worth even thinking about.

But once we moved to northern San Diego County things were very different. Large expanses of undeveloped land featured rolling hills and canyons where fire traveled fast and free. The urban sprawl was elsewhere. And sometimes you had to be ready to leave in a hurry.

The first time I prepared to evacuate was during the 1996 Harmony Grove fire, when I stood in my backyard one night and watched a thin line of flame stretching across the horizon to the southeast. At the time, the area between those flames and our neighborhood was largely undeveloped, and I knew that a wind shift and forty-five minutes could reach the backyard where I stood.

So we prepared to evacuate.

I had no idea where to start.

Some things were easy. We moved the cats and a litter box into a bathroom, closed the door, and had their carriers waiting nearby. I called friends in a safer area and cadged an invitation to move in if necessary. I gathered homeowner’s insurance information, vital documents, and a selection of the family portraits from yesteryear that hang on my office walls. I packed much of the china my grandmother painted by hand through her life, some signed with her maiden name and stamped “Bavaria” on the bottom. I boxed the more important photo albums. I figured out how to quickly disengage my computer CPU and packed medications and a change of clothing for each of us. I gathered cat food and my daughter’s lifelong companion, Pooh Bear.

Okay, full disclosure. I also threw in a complete set of my books. The rule of thumb when packing to evacuate (I’d learn later) was not to bother with anything that could be replaced, but I knew on some primal level that if I did have to start over in a post-conflagration lifetime, that small collection would offer great comfort.

I realized as I gathered these few essential and irreplaceable items that everything else was just Stuff. The realization was strangely liberating.

Then we waited.

Back in that Internet-free era, television was the only information source offering immediacy, but mostly what TV offered was endless loops of the same footage, the same closed roads, the same frightened horses being led into the stables at the Del Mar Fairgrounds.

We never did evacuate that time, nor on any subsequent occasion when I have repeated the drill. And after the first time, packing to evacuate became really easy. These days there are more electronics involved, of course, and more medications, but the basics remain the same: living creatures and that which can’t be replaced.

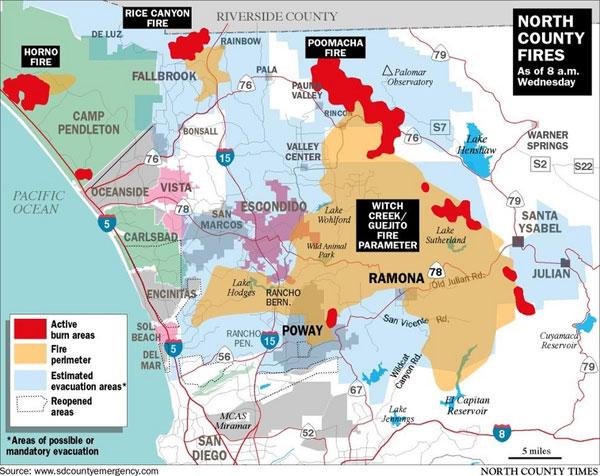

I take it seriously. I’ve known folks who were burned out, or only narrowly escaped. In the Harmony Grove Fire, flames zigzagged around a cul-de-sac where friends lived, sparing their house while leveling the ones next door and across the street. And in 2007 when the Witch Creek Fire and a half-dozen lesser blazes raged throughout North County, the local high school became an evacuation center for folks further inland. Our church across the street served as the staging area for donations, which poured in as SUVs offloaded crates of water, bags of clothing, toys, magazines and a dizzying array of snack food and nonperishables.

I had already packed up when I went down to help at the church, a speedy and streamlined procedure by this point. Because, as I reminded my daughter when she packed to evacuate for the first time, once you set aside the few irreplaceable items that truly matter, it’s all just Stuff.