The Alaska Taxidermy Shop

by Taffy Cannon

We found it purely by chance, tucked into a mid-block covered pathway leading from one downtown street to another in Ketchikan, an Inside Passage waterfront town so remote from both the rest of Alaska and the continental US that it might be on another planet. It had never occurred to me that I would encounter a taxidermy store here—in the middle of the largest North American rain forest in a town that prides itself on excessive rainfall, a lengthy association with the salmon industry and a very nice totem pole museum.

But here we were.

Pelts from all manner of animals: in piles, in bins, hanging on racks. Some were large enough to require folding.

Jackets and moccasins and intricate butter-soft wedding dresses of fringed and beaded leather. Thick fur caps displayed on deer antlers near stern signs forbidding try-ons for photo purposes. All manner of fish in dramatic mounts hanging on a wall above displays of intricately designed and crafted mittens and mukluks.

Oh, and a whole lot of dead animals, brought back to a form of faux-life through loving taxidermy. The animals stood, crouched, clutched captured prey in their mouths and hung on walls, sometimes clear down to the midsection as if bursting through the wall.

It was way beyond overwhelming.

We arrived with other tourists newly disembarked from a couple of large cruise ships docked nearby. A man and woman behind the counter rang up sales, answered questions and took care of business. It was all too much. We left, walked around town in light persistent rain and found the soggy totem pole museum and the salmon ladder and the former whorehouse on Creek Road.

All the while, those animals kept marching around in my mind. Or, actually, standing perfectly still in my mind.

So we went back.

This time the store was deserted and the woman alone behind the counter of what was essentially a single large room, filled to overflowing with the preserved skins and bodies of animals.

For the first time I recognized the depth as well as the breadth of this collection. It seemed to feature nearly every creature that had ever walked or swum in Alaska. Birds were underrepresented, usually appearing only in the mouth of a predator. I learned that the man we’d seen earlier was the taxidermist, father of the woman at the counter. He had gone off to continue taxiderming, an intriguing notion all by itself. What was he working on now?

Some of his handiwork reminded me of whimsical expressions I’d seen on deer in a game room at Shelburne Farms in Vermont while researching Fall Into Death. Around the same time, I’d learned as much as I really wanted to know about taxidermy from a former student, including the art of expressioning the deceased, and it was enough to make me appreciate that this guy was pretty darned good.

Or maybe he wasn’t.

How would I know, after all? I’d never been in a taxidermy shop before, had only seen TAXIDERMY signs on nondescript buildings in small towns, places where you dropped the remains of your butchered buck off in the back. That was a service for hunters; this was a specialty shop for tourists, offering shipping anywhere.

I should explain that I grew up in the brutal winters of Chicago and now live in a climate where winter wear is not an issue. I own only two fur items: a bunch of scraps of something dark brown that looks expensive from a church rummage sale, and a black Persian lamb scarf from the estate sale of Gloria Winters, the actress who played Sky King’s niece Penny. (Yes, really.)

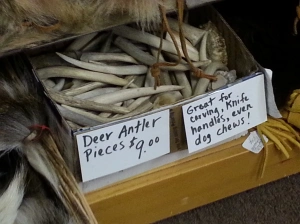

This time, alone in the store, we could see the incredible detail and range of what the place had to offer, from a standing bear to a bin of deer antler chunks for sale at nine bucks apiece: “Great for carving, knife handles, even dog chews!”

I also noticed details I’d missed earlier, as well as an omission or two. I had long been fascinated by the notion of animals which put on a white winter coat to elude predators in the frozen north, and was relieved to confirm that there were no full or partial polar bears on the premises. I was also nonplussed that a white Arctic fox had been marked down to $995 from $1400, and fascinated by a group of virtually identical white Arctic weasel pelts at $25 apiece. I’d never heard of Arctic weasels, but it later turned out I knew them by their haut couture name, ermine. It was appalling to consider how many of these tough little critters with the super-soft white fur would be necessary to make a single ermine coat.

As I looked at piles of pelts from everything from beavers to otters to musk oxen, I began to fully appreciate the role of fur-trapping and the fur trade when Europeans were opening the North American continent and inventing Manifest Destiny. I could also see that back in those days before central heat and Polartec it would be mighty useful to have winter garments of fur if you lived in a place that got really cold in winter and stayed that way for months on end. You’d also want some pretty heavy furs as laprobes if you were riding in a vehicle drawn by horses or dogs. And maybe something to drape over your shoulders if you happened to be riding the horse.

The other things I took away from this array of pelts were a renewed appreciation for the size and scope of Alaska, and a reassessment of what I had previously regarded as an unseemly disregard for preserving its natural wonders. While I might not agree with the philosophy, I could better understand some of the Alaskan attitude toward the environment and regulation from afar: get out of my face, my business, and my life.

Its natural wonders (wildlife included) now seemed as vast as the state itself, the size of which can only be fully appreciated on a globe. It is, after all, a place where most spots are accessible only by small plane and where small planes crash and/or disappear with some regularity. (Cf. Will Rogers, Wiley Post, and House Majority Leader Hale Boggs.)

I wanted something from this place, wanted to support it without participating too actively in the death of an Alaskan creature, but I kept drawing the line. Did I really need fur-lined moccasins for winter in Southern California? How could I buy that sad but beautiful Arctic weasel, knowing that another would be hunted to replace it for the next customer? About the most neutral items in my price range were the deer antler pieces, but I didn’t want one and didn’t have a dog anyway.

Then I saw my answer on the counter. Earrings, my default souvenir from almost anywhere, crafted into darker-than-amber miniature rosettes from thin sheets of cedar bark by a Ketchikan native.

And so I left with flowers, not fur.